Nigeria's energy crisis epitomizes the conundrum of African underdevelopment. As the continent's largest oil exporter and 10th biggest oil producer on earth it should by rights have achieved full energy independence many decades ago. Instead we find a country almost entirely bereft refining capacity, and one that was until last year so dependent on subsidized fuel imports that the removal of that's ame subsidy caused a runaway cost of living crisis./ Fortunately we don't need to look far for an answer, since a recent drama that has dominated the Nigerian business news headlines reveals to us exactly why this is. It concerns the story of Aliko Dangote, Africa's richest man, and how his efforts to disrupt the Nigerian refinery industry have helped reveal for all the world the web of corrupt networks which have conspired to keep Nigeria underdeveloped.

Nigeria, like many other emerging markets of its kind, is a land of opposites. On the one hand it appears poised for great success, with a young population, steadily growing middle class, vast oil wealth and considerable pull with investors interested in Africa's burgeoning tech and financial startup scene. Conversely, its infamously unscrupulous leadership appears bent on scuttling all these advantages. The proceeds of crude oil exports, prioritized above any other sector of the economy are by and large lost to corruption. Underinvestment in infrastructure and economic development unrelated to oil has stifled industrialization, leaving the overwhelming majority of the population dependent on what hand to mouth existence can be eked out of the informal economy.

Some individuals, Aliko Dangote foremost among them,, have leveraged this entrepreneurial spirit to earn great fortunes. Many others however are scarcely able to meet their most basic needs..Of the country's roughly 250m people, 40% are estimated to live in poverty and 26 million suffer from acute hunger. What's worse, the country's economy is not growing fast enough to tackle these issues.Low productivity, high inflation, a lack of reliable utilities, currency volatility and chronic physical insecurity have all served to throw cold water on the once rapturous optimism that lured so many foreign companies to the country's shores in the early 2000s. Many name brand companies are now exiting en masse and skilled graduates are following hard on their heels.

Despite all these challenges, There are still however many enterprising Nigerians intent on helping turn the ship around. For years,despite repeated attempts at revitalisation, the government's four state owned refineries at Port Harcourt, Kaduna & Wari had sat moribund. Then, in 2013, authorities broke with decades of orthodoxy and began to allow for private refinery construction & ownership in an attempt to jumpstart local value addition. Ten years on, and this policy has begun to bear its first fruit, with over 10 refineries in the country either completed or nearing completion. Most of these operations could only be classified as “modular refineries” Small scale operations that require limited capital investment. All with the exception of one, very notable project.

Best laid plans.

When Aliko Dangote, The world's richest black african and the continent's richest man unveiled his plans for the eponymous Dangote Oil refinery in 2013 the news made waves throughout the global downstream oil sector. The facility was going to be gargantuan, a 660k barrel per day behemoth that would outmatch not only every other refinery in Africa, but in Europe as well. Such a project would have required an individual possessed of immense financial and political capital to bring it to fruition, and Dangote had both. The scion of a well- to -do Hausa trading family whose wealth stretched back to before the countries independence, Dangote had already enjoyed immense success as an industrialist in other staple sectors like cement, textiles, sugar , flour & pasta, and was well known to have had the ear of particularly every administration since the end of military rule in 1999. Nigeria thus seemed all but set for a new era of energy independence.

Ten years on however, Dangote’s magnum opus may have turned out to be far more trouble than it was worth. The first issues reared their heads during the initial construction,, which ultimately turned out to cost double its initial projections and whose costs are still partially outstanding. The biggest issues have however been operational ones. At the time of writing the refinery remains well below its utilization target,primarily because it lacks its most important feedstock - crude oil. This ironic conundrum for a facility located in one of the world great oil producing countries largely comes down to broken promises made to Dangote's management in the lead up to the facilities operationalisation. Foremost among these are the the failures, involuntary or otherwise, of The Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) ,a junior partner originally brought onboard with a 20% stake who have under-delivered spectacularly in their original pledge to ensure a reliable crude supply. (For reference, the Dangote refinery will require 15 crude shipments in september 2024, the NNPC will only be able to supply 6)

Following this the refinery had attempted to plug this shortfall by reaching out directly to local oil majors, referred to domestically as IOC’s (International Oil Companies). These attempts were also rebuffed, with producers either claiming to have no excess supply to sell or refinery officials simply finding themselves being pawed off to the oil majors trading desks , where they were duly informed that the exorbitant markup they would need to pay ($4-$6 power barrel) would negate the point of buying domestically at all. While Dangote desperately scrambled to secure some kind of legal mandate to access crude domestically, his facility was forced to source oil from destinations as far afield as Brazil & the United States, a ridiculously circuitous form of procurement in a country that produced over a million barrels of crude on any typical day.

According to Dangote himself, this series of misfortunes were not pure coincidence. Instead, he has publicly stated that these mishaps were an act of deliberate, coordinated sabotage, done on behalf of what he referred to as an “Oil Mafia” ,A politically protected cabal of fuel importers who benefit from many millions in state subsidies and who would stand to lose out significantly if Dangote’s dream of an energy independent Nigeria was to be realised. Such an assertion may initially come off as somewhat conspiratorial, but Dangote has nevertheless received public backing from The Crude Oil Refinery Owners Association of Nigeria, (CORAN), whose members claim to have long suffered under similar underhanded tactics.

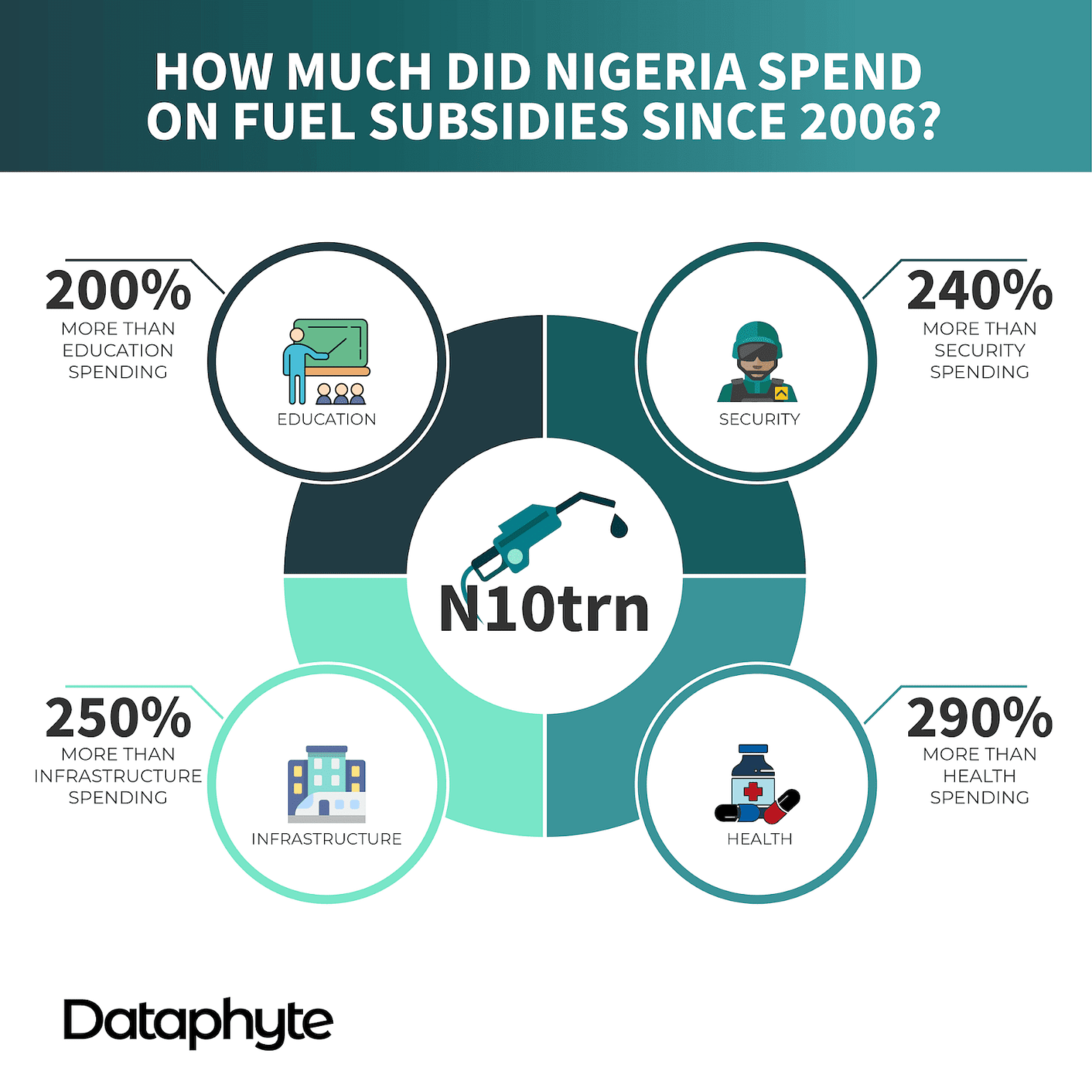

The level of malfeasance surrounding the country's fuel import subsidy scheme represents the pinnacle of corruption in an extremely corrupt industry. From decades of oil spills that have ruined the ecology of local wetlands to large scale oil theft to the underpayment of taxes & royalties in exchange for bribes by oil majors, Nigeria's oil industry enjoys a reputation as sullied as what it pumps from the ground. Little however matches the sheer scale of graft that surrounded the recently shelved fuel import subsidy scheme. This policy, originally implemented in the 1970’s as a compassionate measure to shield the average Nigerian consumer against volatiles in the price for processed fuel, had by 2022 ballooned into an expense that claimed no less than 40% of the national budget, with most of that in turn being siphoned off by corrupt industry and government insiders. Small wonder then that authorities had so long been lackadaisical about restarting state owned refineries, or simply not allowing private refineries the ability to fill in the gap themselves.

All this goes a long way to explain why local actors have been so unreliable in their crude shipments, but why would foreign commodity traders be equally hesitant? These companies are after all quite infamous in their disregard for politics. Major fuel traders operating on the continent have in the past been willing to fund rebel factions and assist sanctioned regimes,so what would they have to lose from a fully functional Dangote refinery? Upon closer inspection, it turns out quite a bit. This is because all over the world different crude variants are not made equal. Nigerian oil, known by its industry moniker of “Bonny light” is particularly prized for being both “sweet”(free of sulfur) and “light” (of lower viscosity) Such a fuel is particularly cheap to refine and easy to transport, meaning that those with access to it can earn better margins for their fuel on the market. Should the Dangote refinery begin pulling its full capacity of feedstock from local sources, many large refineries in Northwest Europe would find their bottom lines adversely impacted, no small issue in a time when refinery margins are shrinking and many are closing shop.

A shoe on the other foot?

While the above makes for an interesting drama, it's important to remember that Dangote is no stranger to charges of corruption himself. Claims of monopolistic activity have dogged him his entire career, most prominently in the cement industry where he made his original fortune and where critics have charged him with regular price gouging after having succeeded in cornering the market. Through his connections he has also been known to acquire special favours, something was thrown abc into the spotlight in january of this year when his Lagos offices suffered a police raid in the aftermath of allegations that he had gained access to special exchange rates thanks to his connections with an ex central bank governor.

However, None of the recent pushback Dangote has been receiving has to do with Nigerian authorities suddenly discovering their conscience.. Rather it almost certainly comes down to seismic shifts in the country's party politics. . Dangote enjoyed close relations for years with the administrations of Muhammadu Buhari (2015-2023) Goodluck Jonathan(2010-2015) and Oluṣẹgun Ọbasanjọ,(1999-2007), all of whom were Peoples Democratic Party candidates. The fortuitous timing of People's Progressive Party leader Bola Ahmed Tinubu victory after a tightly contested election in 2023 and the beginning of Dangote's regulatory woes is quite notable. And likely reflects a deliberate attempt of the new administration to sideline someone they feel is a close associate of their political rivals.

The way ahead.

Meanwhile as the elephants fight, the grass suffers. When Bola Ahmed was elected as Nigeria's new incumbent in May 2023 his first priority was to try and stem the country's growing fiscal crisis, a knock on effect of a deeper economic slump which had only accelerated after the shocks of the covid and post ukraine war periods. First priority was to reign in the country's runaway budget, which required ripping off expensive band aids like fuel subsidies and currency controls. These methods were certainly necessary - since not only had they been ruinous to the budget but they had also often benefited the political elites over the average person.

Nevertheless, their sudden removal hit the economy like a shockwave, making a bad situation much worse for the country's poorest. The cost of fuel and other imports spiked overnight, suddenly placing staple essentials beyond the reach of many. With local refining capacity wholly insufficient to plug the gap, the local downstream fuel sector had no choice but to pass these added costs onto their final customers. The result for already overstretched consumers was calamitous. The pump price jumped from around ₦185 per litre to over ₦500 per litre in some cases.This dovetailed with similarly catastrophic food price inflation,which stood at a whopping 40% in June of 2024.

Public anger has been immediately apparent. In both February and August of 2024, the country was rocked by mass protests against the cost of living and corruption.Security forces responded with a characteristically heavy hand, with the most recent incidents of protests leading to 22 deaths, over 7000 arrests and a dozen protestors on trial for treason. Such excess naturally does little to earn the love of the public, and does nothing to curb the population's more radical responses to what they perceive to be the inherent unfairness of their society. While Nigeria is Africa's biggest economy, it is also a hotbed of violence, a society beset by criminality and radicalism of all kinds, from secessionist movements & rural banditry to inter community violence over rights and religious militancy. It goes without saying that the persistence of corruption and poverty, and the security forces' apparent allegiance to such a system will only serve to fuel more radicalism.

By 2050, Nigeria will be the world's third most populous society. This offers it one of two choices. It can harness its existing potential ,advance up the economic value chain and become a world straddling economic powerhouse like India or China, or it can embrace its current status quo and slouch further down the path of corruption and lost potential. Nigerian elites do not have long to decide. If they cannot provide millions of new young Nigerians the prosperous future they deserve, those same young people will simply turn towards others who claim they can. Ongoing conflagrations in nearby countries like Niger, Burkina Faso & Mali, where pro Russian juntas are fighting losing battles against some of the world's most active islamist insurgencies, stand as testaments to what that could look like. As stewards and custodians of West Africa's largest economy, the decisions of Nigerian elites will inevitably impact not only the rest of the region but also the world at large in the coming years. Let's hope the decisions they make are the right ones.